SCA interns – and sisters – Megan and Katie Woods are researching rarely recognized yet essential moments in US history at the National Parks of Boston. In a fortuitous turn, their work coincides with this, African American History Month, and March’s Women’s History Month. Here is Part One of their absorbing look back – and ahead.

Boston’s history has long been synonymous with the American Revolution. When people come to Boston, many expect to hear stories of Paul Revere, Samuel Adams, John Hancock, and other leaders of the battle for independence. Yet Boston’s history does not end with the American Revolution. The National Parks of Boston is working to expand beyond this narrative by highlighting the stories of people of color and women in the city’s later social and political movements.

To achieve this, the National Parks of Boston designed SCA Public History Internships to research often overlooked histories. The 2019-2020 research projects, “The Great Migration and Charlestown Navy Yard” and “Suffrage in Black and White,” focus on expanding the presence of African American and women’s voices on Boston’s historical landscape.

As public historians and recent graduates of Northeastern University’s Public History Master’s Program (and yes, we’re twins!), we jumped at the chance to work with the National Parks of Boston, eager to dive into these chapters of Boston’s history. In our studies, we’ve always been drawn to the little known and overlooked voices in history; the voices that have been often presented as a side note and not integrated into the teaching of U.S. history. By embracing these stories at historic sites, we can tell more inclusive and relevant narratives that reflect the diversity of our country. We, and the National Parks of Boston, hope that everyone can see themselves in the stories we share.

In this multi-part blog, we will both share our individual research, the challenges we have faced, and the public-facing programs and digital materials we have been creating with this research.

Great Migration and the Charlestown Navy Yard

by Megan Woods

Since the beginning of my internship, I have been searching for a needle in a haystack.

Sifting through archival documents, scrolling through newspapers on microfilm, and flipping through census records are just some of the ways I’ve spent hours searching for little nuggets of information that shed light on the connection between the Great Migration and the Charlestown Navy Yard.

The Great Migration refers to the thousands of African Americans who left the South seeking economic advancement and fleeing race discrimination in the 20th century. Many of these African Americans found jobs in the defense industry, including shipyards. When I first started this internship, the National Parks of Boston suspected this relationship existed, but had yet to dive into the research. Tasked with this research topic, I have been trying to find evidence of this connection.

How do you start researching a topic so niche, yet so integral for telling a diverse narrative at an historic site? First, I turned to secondary sources. Very little scholarship exists about African American workers at the Charlestown Navy Yard, let alone the Great Migration in Boston. However, reading various literature on these general topics and Boston’s African American community oriented me to my topic’s historical context and sparked ideas for primary sources to investigate. These primary sources, from newspapers and census records to archival collections and government case files, have been at the core of my research. These documents have led me to the lives of several different Southern black migrants of the Great Migration who worked at the Navy Yard. One of these individuals was Helen Lee Franklin.

Helen Lee Franklin

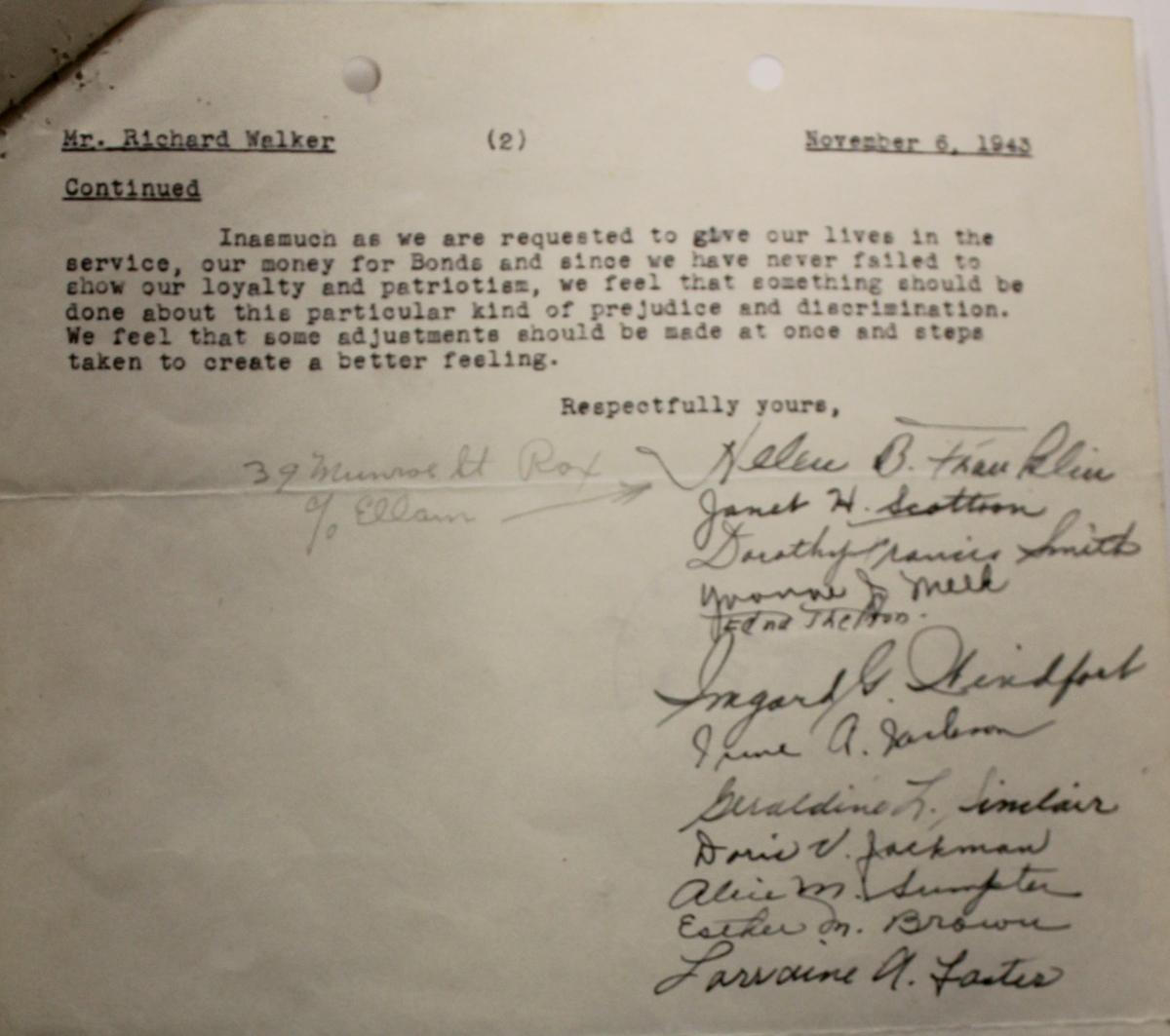

I learned of Helen when looking through Fair Employment Practices Committee (FEPC) discrimination case files from the National Archives of Boston. President Franklin D. Roosevelt established this organization to fight racism in the defense industry, so African American workers submitted complaints to this Committee for it to investigate. Helen Lee Franklin and 11 other women sent their complaint to the FEPC in November of 1943, stating that they believed their section was becoming segregated and that their supervisors gave white women promotions before them. Reading about this case sparked my curiosity in Helen Franklin, a woman who organized other women to fight against discrimination at the Navy Yard. I had to find out more about her.

The case file had only her name “Helen B. Franklin” and a current address in the Boston neighborhood of Roxbury. I tried searching through census records to no avail; however, I did find a few city directories listing her at this address living with her husband, Clarence Franklin. Even after looking into Clarence, I hit a dead end. A couple months later I unexpectedly came across a few letters from and to Helen in Julian D. Steele’s archival collection at Boston University. Julian D. Steele, President of the Boston Branch of the NAACP during World War II, directly wrote to Helen about discrimination at the Navy Yard, giving me a clear indication that this was indeed her. And this time, I had a maiden name “Lee” to help me with my search.

The last page of Helen Franklin and her colleagues’ letter to the Fair Employment Practices Committee regarding discrimination at the Navy Yard. (National Archives at Boston)

Yet once again, I hit a brick wall. I had found a few census records listing a Helen Lee from South Carolina (part of the Great Migration!), but I had no way to know whether or not this was her. I had also found an article that mentioned her as an individual’s aunt, but nothing more. I decided to set her aside for a little while with the hope that I would think of a new way to track her down. Sometimes you need a break to allow your mind to think of new ways to reapproach your research. And then it hit me, why don’t I look into her nephew? Researching this nephew, Clarence Elam, allowed me to track down a census record. In theory, his mother, Blanche Elam, would be Helen’s sister of the same maiden name Lee. With that information I could confirm that the census records I had previously found were indeed the same Helen Lee, Helen Lee Franklin, from the initial FEPC case file.

With this new information, I could identify the year she passed away: 1949. Hoping to find her obituary, I went to the Boston Public Library to start scrolling through microfilm of the Boston Chronicle and the Boston Guardian, two prominent black newspapers at the time. When I came to the end of January I found it; both newspapers had obituaries for Helen Lee Franklin! The Boston Chronicle had a thorough obituary describing how she came to Cambridge, Massachusetts with her family as a young girl from South Carolina, yet moved to the South to work at two different all-black schools. When she returned to Massachusetts, she became involved with several community and political organizations, including the Cambridge Community Center, the Boston Urban League, and the Boston Branch of the NAACP. Looking at the organizations she supported within her community makes it clear why Helen stood up against discrimination and racism at the Charlestown Navy Yard.

Even though I found all of this information about Helen, the search continues. While I’m still filling in the gaps of her life, I can clearly see she was a dedicated activist and organizer of her community. For Helen and the other workers I have researched, the Navy Yard played varying roles in their lives; some southern black migrants only worked at the Navy Yard during World War II, while others had decades-long careers. My research often takes me beyond the Navy Yard, into the communities as I uncover these individuals’ stories. With a lot of research and even more luck, I have begun to connect the dots between the Great Migration and the Charlestown Navy Yard.

Looking Forward

In order to share these stories, I am currently working on a couple of different public-facing projects. Throughout the spring I will be sharing this research through talks at another National Park, Boston Public Library Branches, and the Charlestown Navy Yard. In this talk I focus on discrimination at the Navy Yard, questioning whether Southern black migrants truly escaped the racial discrimination of the South when they made their way to Boston and the Charlestown Navy Yard. Similarly, I am working on an article about two African American women who fought back against discrimination at the Navy Yard to demonstrate how the fight for women’s rights continued after the passage of the 19th Amendment.

Megan presenting her talk “From Migration to Discrimination: African American Workers at the Charlestown Navy Yard.” (NPS/Hornbeck)

Since every Southern black migrant’s story is different, I am also working on a series of digital story-maps about some of the individuals I have researched during this internship (yes, one will be about Helen Franklin!). While these story-maps will be unique to each person, I hope to highlight different aspects of the Great Migration within their stories. These digital story-maps will make the stories of these Navy Yard workers more accessible to the larger public as well as help diversify the stories shared at the Charlestown Navy Yard.

Next: Suffrage in Black and White, by Katie Woods